Introduction

In research, measuring something that is not directly visible—like motivation, job satisfaction, or stress—can be challenging. This is where scale development comes in. Scale development is the process of creating a reliable and valid set of questions (items) that help researchers measure these invisible concepts, also known as constructs.

For example, if a researcher wants to study student motivation, they can’t just “look” at motivation. Instead, they design a scale with questions like:

“I feel excited to attend my classes.”

“I set personal learning goals regularly.”

When used correctly, scale development ensures that the data collected truly reflects what the researcher wants to study. This blog explains the steps of scale development in simple language, with examples from real-world research.

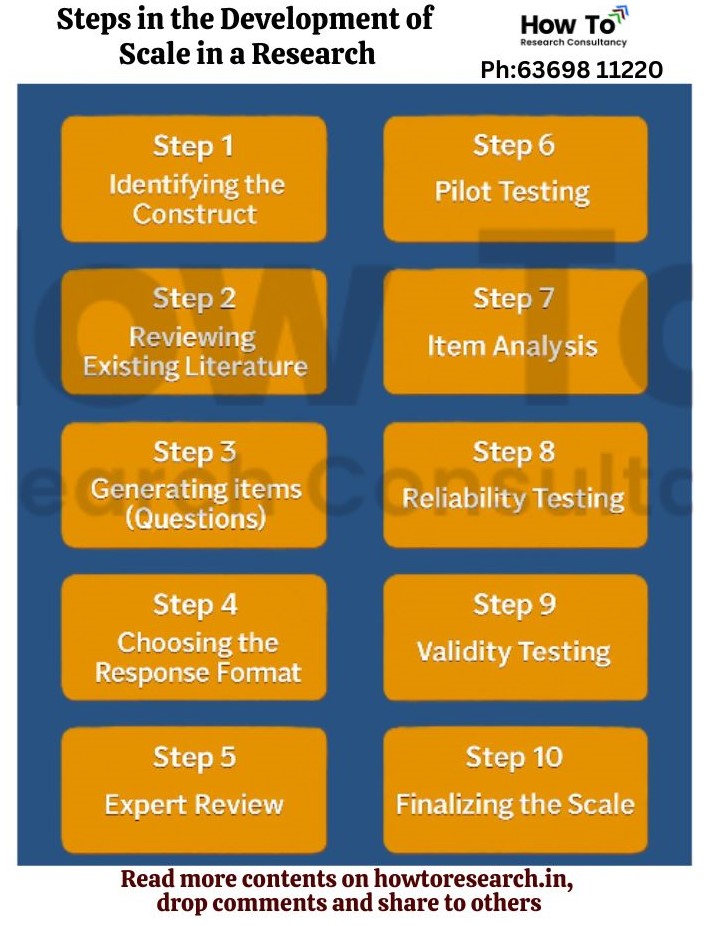

Steps of Scale Development

Step 1: Identifying the Construct

Before developing a scale, the researcher must clearly define what they want to measure. This is called identifying the construct.

Example:

Suppose you want to measure employee job satisfaction. You first need to decide: What does “job satisfaction” mean in my study?

Is it about salary satisfaction?

Work-life balance?

Opportunities for growth?

Once you have a clear definition, you can move on to building the scale.

Step 2: Reviewing Existing Literature

A good scale is often built on existing research. Reviewing previous studies helps you understand how other researchers have defined and measured the construct.

Example:

If you are creating a Stress Management Scale, you might find that earlier researchers measured it using items related to relaxation techniques, time management, and emotional control. You can adapt some of these ideas instead of starting from scratch.

Step 3: Generating Items (Questions)

This step involves writing a list of potential questions (items) for your scale. Items should be simple, clear, and directly related to the construct. Avoid double meanings or jargon.

Example:

For a Customer Loyalty Scale, you might write:

I recommend this brand to my friends and family.

I prefer this brand over others, even if it costs more.

I will continue buying products from this brand in the future.

Step 4: Choosing the Response Format

Researchers must decide how participants will answer the questions. A common choice is the Likert scale (e.g., 1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

Example:

In a Work Engagement Scale, you might use:

Strongly Disagree (1)

Disagree (2)

Neutral (3)

Agree (4)

Strongly Agree (5)

Step 5: Expert Review

Once you have your initial set of items, it’s important to have experts review them. Experts can check if the questions are clear, relevant, and free from bias.

Example:

If you’re developing a Social Media Addiction Scale, you could ask a psychologist and a social media researcher to review the questions before testing them.

Step 6: Pilot Testing

Pilot testing means trying the scale with a small group of people from your target population to check if the questions make sense.

Example:

If your target audience is college students, you might give the pilot questionnaire to 30–50 students to see if they understand the items and response options.

Step 7: Item Analysis

After collecting pilot data, researchers analyse the responses to identify which items are performing well and which should be removed. This can involve statistical methods like item-total correlation or exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

Example:

If an item on your Leadership Skills Scale has very low correlation with the total score, it might not be measuring leadership effectively and should be dropped.

Step 8: Reliability Testing

Reliability means the scale produces consistent results. One common measure is Cronbach’s alpha (values above 0.70 are generally considered acceptable).

Example:

If your Teamwork Scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85, it means your items are strongly related and measure the same construct consistently.

Step 9: Validity Testing

Validity checks whether the scale actually measures what it claims to measure. Common types include:

Content validity – Experts confirm the items cover all aspects of the construct.

Construct validity – Statistical tests confirm the scale measures the intended concept.

Criterion validity – The scale correlates well with other established measures.

Example:

If your Job Stress Scale scores are strongly related to absenteeism rates, it suggests good criterion validity.

Step 10: Finalising the Scale

After ensuring the scale is reliable and valid, you can finalise it for wider use. A good scale should be clear, concise, and easy for respondents to complete.

Practical Example: Developing a “Healthy Lifestyle Scale”

Identify construct: Healthy lifestyle = physical activity, diet, sleep habits, stress management.

Review literature: Look at WHO health guidelines and past health behaviour scales.

Generate items:

I exercise at least three times a week.

I eat at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily.

I sleep for 7–8 hours each night.

I use relaxation techniques to manage stress.

Choose format: 1 = Never, 5 = Always.

Expert review: Nutritionist and fitness trainer review items.

Pilot test: 40 adults complete the survey.

Item analysis: Remove items with poor correlation.

Reliability test: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88 (good).

Validity test: Compare with existing physical health measures.

Final scale: 12 items, ready for use in health research.

The following image provides the all the steps for the development of a scale:

Adoption, Modification, and Development of Research Scales

In research, the generally accepted practice is to adopt an existing validated scale when it aligns perfectly with the construct, context, and target population under study, as this ensures reliability, validity, and comparability with prior research while conserving time and resources (DeVellis, 2017). When minor contextual, cultural, or linguistic adjustments are needed, researchers may modify the original scale, provided the adapted version undergoes re-validation for reliability and validity (Hinkin, 1998). If no suitable instrument exists, researchers should develop a new scale through item generation, expert review, pilot testing, and psychometric evaluation, ensuring it accurately captures the construct (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). The preferred order is: adopt if fully suitable, modify if partially suitable, and develop new when no valid option exists (Boateng et al., 2018).

Need for Contextual Validation

Even a highly reliable and valid scale may not perform accurately in a different country, industry, respondent group, or time period due to variations in cultural, linguistic, social, and temporal factors. For instance, a customer service quality scale from the U.S. airline industry in the 1990s may not effectively measure e-commerce service perceptions in India in 2025. Changes in technology, consumer behaviour, and industry norms can alter the relevance of scale items. Therefore, experts recommend contextual validation involving translation (if necessary), cultural adaptation, pilot testing, and statistical checks for construct validity, reliability, and measurement invariance before applying a scale in a new setting (Hinkin, 1998; DeVellis, 2017). Without this process, even a previously validated scale may fail to reflect the realities of the current research context.

Permission to Use or Modify Scales

The measurement instrument used in a study may be subject to copyright, and the need for permission depends on the scale’s licensing status. If the scale is publicly available or free for academic use, it can be adopted or adapted with proper citation (American Psychological Association, 2020). However, for copyrighted scales, researchers must seek permission from the copyright holder, particularly when reproducing items, translating, or making modifications (Streiner, Norman, & Cairney, 2015). Ethical practice also encourages informing the original authors out of professional courtesy.

A short, formal note we can directly include in our methodology section:

In the present research, the scale developed by [Author(s), Year] was [adopted/adapted] with [explicit permission/public-domain authorisation], ensuring compliance with legal and academic requirements (APA, 2020; Streiner et al., 2015).

Conclusion

Scale development in research involves deciding whether to adopt, modify, or create a measurement instrument, with adoption of an existing validated scale preferred when it fully matches the study’s construct, context, and population, ensuring reliability, validity, and comparability. When contextual, cultural, or linguistic differences exist, modification is acceptable but requires rigorous re-testing, while new scale creation—though time-intensive—becomes essential when no suitable tool exists.

Even validated scales may lose accuracy when applied in different settings due to cultural, linguistic, or temporal changes, making contextual validation crucial. Additionally, ethical and legal compliance requires obtaining permission to use or adapt copyrighted instruments and properly citing all sources. Ultimately, careful selection, contextual validation, and adherence to intellectual property rights ensure the development of reliable, valid, and contextually relevant tools that accurately capture the concept under study.

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

DeVellis, R. F. (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819800100106

Streiner, D. L., Norman, G. R., & Cairney, J. (2015). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127

Leave a Reply