Whether you are exploring consumer behaviour, studying climate change, or testing a new teaching method, research design forms the foundation of how you collect, analyse, and interpret data. It is essentially the blueprint of any study, ensuring that the evidence gathered addresses the research questions effectively, systematically, and ethically.

In this blog, we’ll break down the meaning of research design, its types, and practical examples across various fields—ranging from social sciences and healthcare to marketing and education.

What is Research Design?

Research design is a structured plan or strategy that guides researchers in collecting, measuring, and analysing data. It ensures that the study is both valid (measuring what it claims to measure) and reliable (producing consistent results). A well-thought-out research design aligns with the study’s objectives, provides direction, minimizes bias, and enhances the credibility of the findings.

Major Types of Research Design

Research designs are generally categorized into the following types:

- Exploratory Research Design

- Descriptive Research Design

- Explanatory (or Causal) Research Design

- Experimental and Quasi-experimental Design

- Correlational Research Design

- Longitudinal and Cross-sectional Design

Let’s explore each with practical examples.

1. Exploratory Research Design

Purpose: It is used when a problem is not clearly defined or there is limited existing knowledge about the topic.

Its main goal is to gain a deeper understanding, generate insights, and help formulate hypotheses for future research. It is typically qualitative in nature and uses methods like interviews, focus groups, observations, or literature review.

A company launching a new product in an unfamiliar market might conduct informal interviews with potential customers to explore their preferences, buying habits, and unmet needs. Exploratory research is often the first step in the research process, setting the foundation for more structured, quantitative studies that follow.

Example – Marketing Domain:

A tech start-up wants to understand why its new app is receiving low engagement. Instead of jumping to conclusions, the company conducts focus group discussions and informal interviews with users to uncover pain points. The insights help shape future app development and guide detailed surveys.

Example – Sociology:

Researchers exploring the rise in teenage social isolation might start with open-ended interviews and literature reviews before designing a larger quantitative study.

2. Descriptive Research Design

Purpose: It is used to systematically describe the characteristics, behaviours, or conditions of a population or phenomenon.

Unlike exploratory research, it is more structured and focuses on what exists, rather than why or how it happens. It answers questions like “what,” “when,” “where,” and “how much.” For Example, A retail company conducts a nationwide survey to measure customer satisfaction levels and identify shopping patterns across different regions.

This design often involves surveys, observations, or analysis of existing data, and is usually quantitative in nature. It is useful when the objective is to present an accurate profile of a situation, which can inform decision-making or set the stage for causal studies.

Example – Healthcare:

A public health department surveys 5,000 residents to understand the prevalence of diabetes in a city. The study describes patterns based on age, gender, and income levels.

Example – Education:

An education researcher wants to document the teaching methods most commonly used in urban primary schools. The study involves structured observations and questionnaires administered to teachers.

3. Explanatory (Causal) Research Design

Purpose: Seeks to understand cause-effect relationships by testing hypotheses.

It is used to determine whether one variable causes or influences another. It focuses on identifying cause-and-effect relationships by testing hypotheses and observing how changes in one variable lead to changes in another. This design often uses experiments or statistical techniques to control for external factors. For example, a study may examine whether increasing advertising spend directly leads to higher sales.

Example – Economics:

A researcher wants to determine whether an increase in minimum wage leads to higher unemployment. By comparing employment data before and after policy changes, and controlling for other factors, a causal relationship is tested.

Example – Marketing:

A company wants to determine whether offering discount coupons increases customer purchases. It conducts a study where one group of customers receives a 20% discount coupon, while another similar group does not. By comparing the sales data between the two groups, the company analyses whether the coupon caused an increase in purchasing behaviour. This setup helps establish a cause-and-effect relationship between the marketing strategy and customer response.

Example – Environmental Studies:

To assess if banning single-use plastics reduces litter in public parks, the researcher collects data from areas before and after the ban implementation.

4. Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs

Purpose: Both experimental and quasi-experimental designs are used to test cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

They involve the manipulation of independent variables to observe their impact on dependent variables, making them ideal for hypothesis testing under controlled or semi-controlled conditions.

(a) Experimental Design:

It involves random assignment of participants into treatment and control groups. The researcher actively manipulates one or more independent variables and observes the outcome on the dependent variable.

Example – Economics:

Researchers want to test whether providing financial literacy training improves saving behaviour among low-income households. Participants are randomly assigned to two groups: the treatment group receives a structured financial education program, while the control group does not. After six months, both groups are surveyed to measure changes in savings rates, budgeting habits, and financial decision-making.

Example – Psychology:

A study investigates whether a mindfulness program reduces anxiety. Participants are randomly assigned to two groups—one receives the program, the other does not. Anxiety levels are measured before and after the intervention.

Example – Education:

A school wants to test whether using interactive digital learning tools improves student performance in science. The students are randomly divided into two groups—one uses digital learning tools, while the other follows traditional methods. Their test scores are compared to determine if the digital tools caused improved performance.

(b) Quasi-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental designs are similar to experimental designs but lack full randomization. They are used when random assignment is not possible or ethical, yet the researcher still wants to examine causal relationships.

Example – Tourism

A coastal town launches a sustainable tourism campaign, while nearby towns do not.Tourist footfall, spending patterns, and feedback are analysed before and after the campaign to evaluate its effectiveness.

Example – HR/Workplace Research:

A company introduces flexible work hours in one department but not another. Employee productivity is measured across both to evaluate the effect.

Example – Public Policy:

A city introduces a free public transport policy in one zone but not in others. Researchers compare commuter behaviour across both zones to infer causal effects.

5. Correlational Research Design

Purpose: Examines the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them.

It helps determine whether variables are positively, negatively, or not at all related. However, it does not establish causation, only association.

Example – Library Science:

A library science researcher studies the relationship between library usage frequency and academic performance among university students. By analysing data from library visit logs and students’ GPA records, the study identifies whether frequent library use is associated with higher academic achievement—without manipulating either variable.

Example – Business Studies:

A company investigates the correlation between job satisfaction and employee retention. Using survey data, it finds a positive correlation, suggesting that happier employees are likely to stay longer.

Example – Health Sciences:

A researcher explores the correlation between screen time and sleep quality among adolescents. Though a relationship may be found, causation cannot be claimed.

6. Longitudinal vs. Cross-sectional Design

Longitudinal Design: Observes the same subjects over a long period.

It involves studying the same subjects over an extended period of time to observe changes and developments. It is ideal for tracking patterns, trends, or effects over months or years. This design is widely used in education, psychology, and health to understand long-term impacts.

Example – Longitudinal in Medicine:

A 10-year study follows patients with pre-diabetes to understand the progression to type 2 diabetes.

Cross-sectional Design: Collects data at a single point in time.

It involves collecting data from a population at a single point in time to analyse current conditions, behaviours, or attitudes. It provides a snapshot of a phenomenon, making it useful for identifying patterns or differences among groups. This design is commonly used in surveys, market research, and social science studies.

Example – Cross-sectional in Political Science:

A survey captures public opinion about a new law at a specific moment to analyse regional differences.

Why Research Design is important?

Research design is crucial because it provides a clear and structured plan that guides every step of a study—from identifying the research problem to collecting and analysing data. If research design is not followed correctly or is poorly structured, the entire study can suffer from serious flaws—leading to unreliable, invalid, or misleading results.

For instance, if a healthcare study uses a non-random sample to test a new treatment, the outcomes may be biased and not generalizable to the larger population. In business research, using a descriptive design to make causal claims (e.g., claiming an ad campaign caused a rise in sales without proper controls) can result in incorrect conclusions and poor strategic decisions. In education, if a researcher skips proper sampling techniques, feedback from only high-performing schools may distort the understanding of teaching effectiveness.

Such mistakes waste resources, misguide policies, and can damage the credibility of the research. A sound research design ensures that the data collected genuinely answers the research question and supports logical, evidence-based conclusions.

Usage of Combination of Research Designs

A combination of research designs refers to the intentional use of two or more research design types (e.g., exploratory and descriptive) within a single study to better understand a research problem from multiple perspectives. This approach helps in first exploring a problem deeply and then measuring it accurately, enhancing both the richness and validity of the findings. It is especially useful in social science research where issues are often complex and multifaceted.

In social science research, it is both valid and effective to combine exploratory and descriptive research designs within a cross-sectional time frame. This approach is especially useful when the research problem is not fully understood at the beginning. The study typically begins with an exploratory phase using qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups to gain initial insights, identify key variables, or develop hypotheses.

Based on these findings, the researcher then moves to a descriptive phase, often using structured surveys or questionnaires to quantify and analyse patterns among a larger sample.

When this data is collected at a single point in time, the study follows a cross-sectional design, allowing for efficient assessment of current opinions, behaviours, or conditions.

This combined design is widely used in fields like marketing, HR, psychology, and tourism, as it provides both depth of understanding and measurable evidence in one cohesive study.

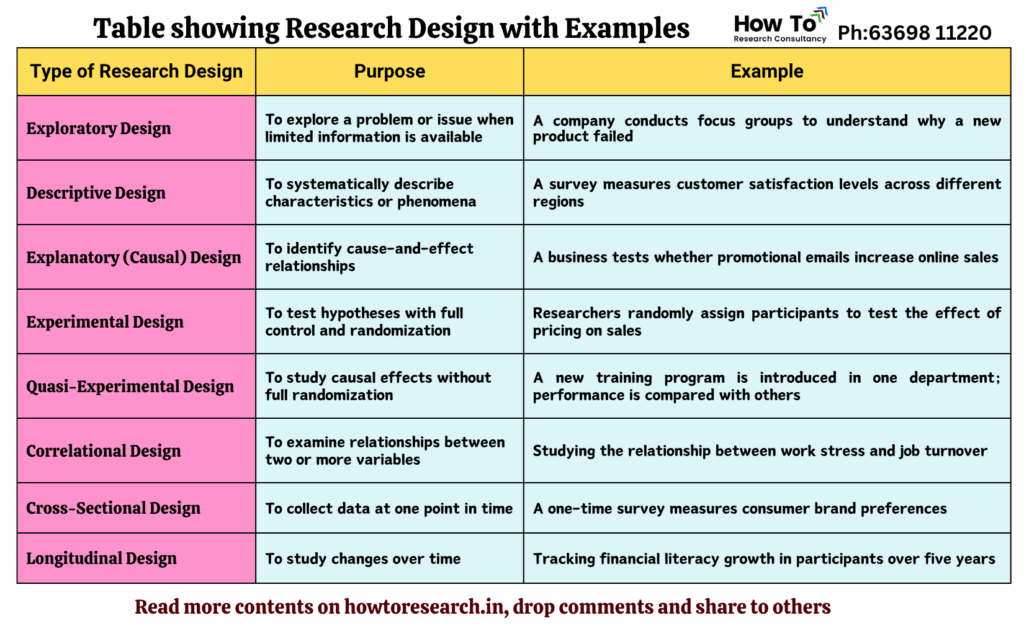

Types of Research Design with Examples

Choosing the Right Design: Key Considerations

- Research Questions: The nature of your question largely determines the design.

- Resources and Time: Experimental and longitudinal designs require more effort and resources.

- Ethical Constraints: In medical or social interventions, ethical approval may restrict certain designs.

- Data Availability: Sometimes existing data limits your design options.

Example – Resource Constraint in Disaster Studies:

A researcher studying post-disaster migration may not have access to displaced individuals for experimental study but can use secondary census data for a descriptive or correlational analysis.

Final Thoughts

Research design is more than a technical step—it is a strategic decision-making process that influences the entire research journey. From formulation to analysis, each design type serves a specific purpose. The key is choosing the one that best aligns with your objectives, context, and constraints.

In a world driven by data and evidence-based decision-making, mastering the art of research design is not just for academics—it’s a valuable skill for professionals across all domains.

Call to Action:

If you’re designing your first study or refining your thesis proposal, take a moment to clearly define your research question and then align it with the most appropriate design. A strong foundation ensures that your findings will stand the test of scrutiny and serve a meaningful purpose.

Need Assistance in developing the right Research Design for your research, contact us!

Leave a Reply